TangoDown Inc.—Vickers Tactical Slide Racker for Large-Cal. Glocks

The GSR-05 Slide Racker is TangoDown’s latest addition to its Vickers Tactical lineup….

The GSR-05 Slide Racker is TangoDown’s latest addition to its Vickers Tactical lineup….

The Chiappa Rhino is one of the most singular revolver designs we’ve seen,…

This past SHOT Show, Midwest Industries presented revolver enthusiasts with a new way…

All shooting is a balance between speed and precision. By that I mean you can…

The Mod-Navy Qual I’ve been doing this qual (or drill, or whatever the current nom…

• Built for road trips and off-road use• Manual transmission equipped• Wrapped in MultiCam Arctic…

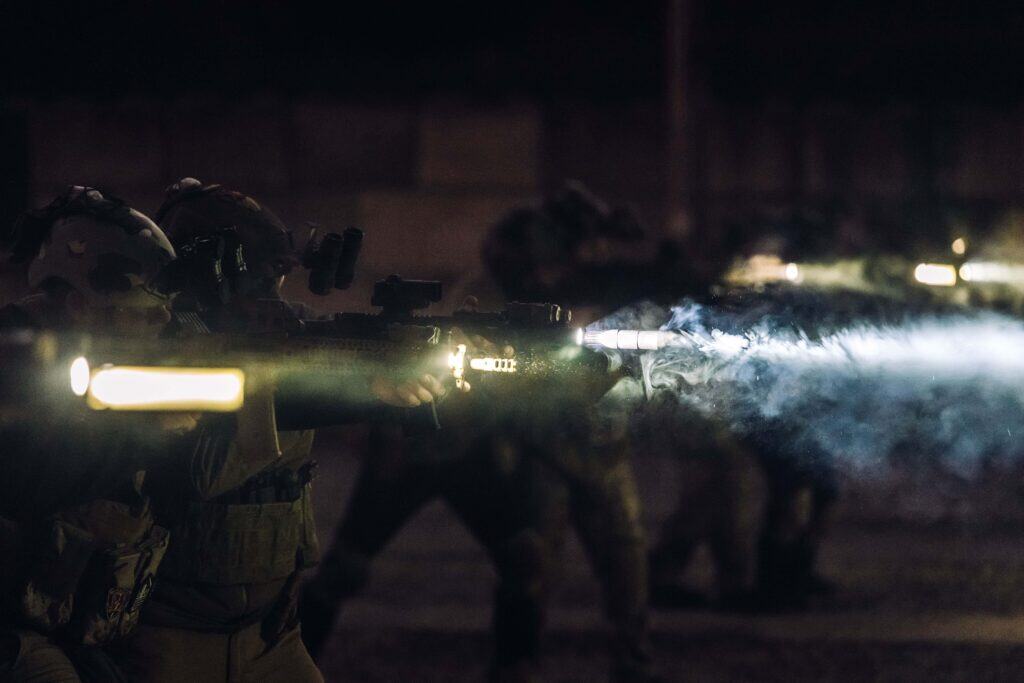

If you can do it in the dark, you can do it in the light. However, the inverse of that statement is not necessarily true. A well-rounded warrior will ensure he can work in all conditions. Bad things don’t always happen under impossibly blue skies with cottonball clouds. In fact, they often occur in poor environmental conditions while under stress. Humans are diurnal creatures. This means that we are biologically predisposed to be active during daylight hours. It is also why we are so reliant on our eyes, receiving more than 90% of our sensory information through sight.

When the lights go out, our world gets real small, real fast. We become tired and begin losing some fine motor skills. We naturally become more scared because we cannot see as much or as far. Our brains expend more energy to process our environment and it takes more effort to accomplish otherwise simple tasks because we are trying to resolve the darker world around us. In essence, operating in the dark produces more challenges than operating in the light.

We have developed incredible technological advancements to help balance the scales when man or Mother Nature turns out the lights. White lights and night vision optics help us see in the dark better than ever. But both technologies come with limitations on the battlefield.

White lights can be weapon-mounted, handheld, headborne, and so on. The candela and lumens produced can vary from less than a hundred to thousands. To put it plainly, artificial light allows us to see in the dark. Unfortunately, it also lets our adversaries see in the dark. And if we are using a white light source on our weapon or our person to search an area or perform an administrative task, we are drawing attention to ourselves from downrange.

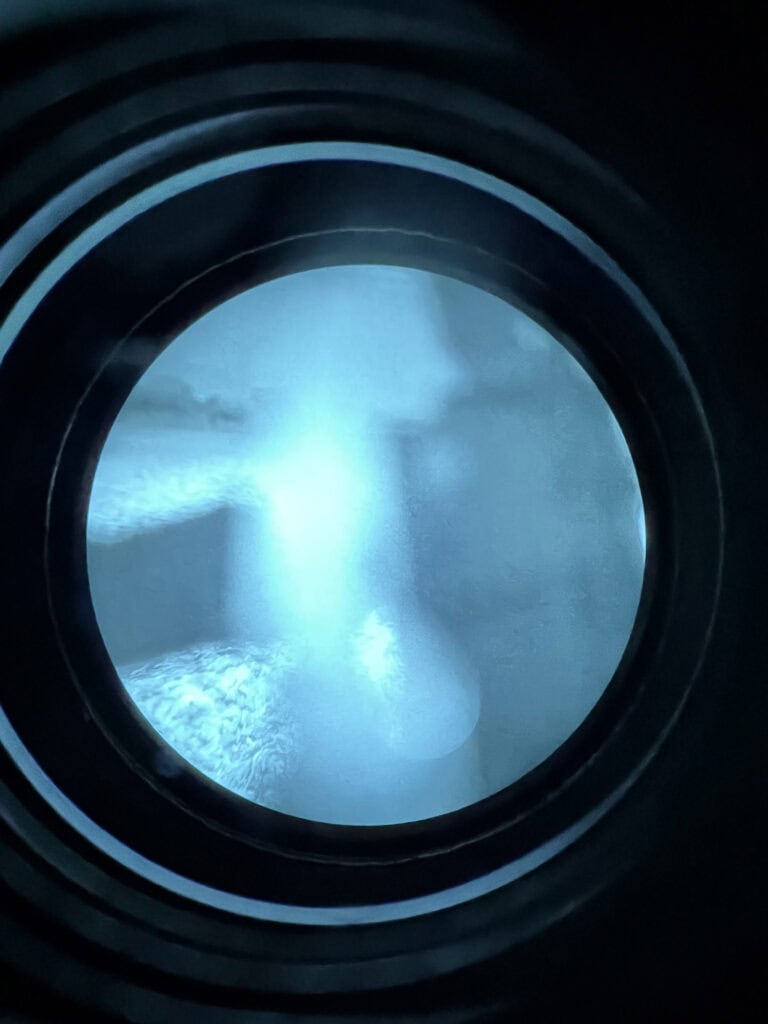

Night vision covers two primary technologies: Image Intensification (I2) and Thermal. Neither of these technologies will produce a signature visible to the naked eye. I2 technology amplifies existing light while thermal detects heat. And while the ability to see in the dark is almost magical, it comes at a price. Most night vision goggles are limited by a 40-degree field of view. And all night vision devices operate on a fixed focal plane.

While our eyes will naturally re-focus near/far, NODs are going to stay focused at the distance set by the user. And that distance is generally going to be about 15 yards to infinity. This means the image will become progressively blurrier as the object gets closer. It also means there is no way to see anything in detail right in front of you while wearing NODs unless you manually refocus the goggle.

While our technologies provide some incredible advantages, we need to understand they come at a price. We need to give something to get something. I’m referring to the understanding that unless we are aware of and take steps to mitigate the limitations imposed by our technology, it will become more of a liability than advantage on the battlefield. Regardless of expensive NODs and high-powered white lights, our performance will still somewhat degrade in the dark. This is simply because our brains are so reliant on sight. It is also precisely why darkness should be the qualifier for any process or procedure we have. If you can do it in the dark, you can do it in the light. But again, the inverse is not necessarily true.

I could probably write a book about every process and procedure in the warfighter world being done at night. But TTPs and SOPs are different from unit to unit, command to command. To illustrate my point about doing it in the dark, let’s look at some individual fundamental skills and how they can be performed in all conditions. When we start our journey down the path of the warrior, we begin with the fundamental skills. Things like marksmanship and weapon manipulation are going to be some of the most relatable topics to readers of this magazine.

Most professional shooting instruction takes place on the square range: a flat, well-manicured field with targets downrange and the sun shining. From a safety standpoint, we must begin almost robotically with every step of a drill or procedure being directed by an instructor. Fundamentals are incredibly important. The best operators in the world are simply performing the fundamentals on demand. There are no secret ninja fundamentals. Where things start getting complicated is when exigent circumstances are introduced. The impossibly blue skies and cottonball clouds over a well-manicured range will never be the battle space in which the fundamentals will be applied in the real world. Therefore, it is imperative that we not expect the procedures learned and practiced here to be what we fall to in the face of a determined opponent in the dark.

A friend and fellow instructor, Will Petty, says, “Your first time shouldn’t be your first time.” This contextual statement should be applied to everything we train for in the warrior arts. In the context of this article, it means “your first time performing a task in the dark on the battlefield shouldn’t be the first time you’ve performed that task in the dark.” If it is, you are way behind the power curve. The world looks and feels different in the dark. And you will quickly find that many of the “fundamentals” popularized by YouTube trainers are not going to work when you cannot see the environment or even your own weapon.

Let’s talk about reloads. As an instructor, I see a lot of students from a lot of different walks of life on my ranges. And I can safely say that the “workspace reload” is still the prevailing method being taught by a lot of agencies and other instructors. The workspace reload is a method for conducting an emergency reload where the shooter brings the weapon (rifle or pistol) up into his “workspace”—the imaginary box immediately in front of the face.

1. The weapon is taken off target and swung up into the workspace.

2. The magazine release button is pressed with the firing hand while the support hand simultaneously strips the empty mag from the gun.

3. A fresh magazine is retrieved and inserted into the weapon.

4. The bolt or slide is released back into battery.

5. The target is reacquired/reengaged.

The concept of the workspace reload is that the shooter can see both the target and the magwell at the same time. This allows him to maintain visual on the threat while “seeing” his magazine into the gun in case he misses the magwell. It’s a solid exercise in the daylight. But it is pointless and inefficient in the dark.

Let’s Dissect It

1. Bringing the weapon into the workspace with the intent of seeing it and the threat in the dark is useless. The naked eye cannot effectively focus on both in the dark, without white light (which the shooter is not going to use during a reload). NODs have a set focal length, which is going to be focused at the engagement distance. A weapon in the workspace will be completely blurry, making the entire movement pointless.

2. The motion of pointing the muzzle at the sky in one’s workspace requires the support hand to strip the empty mag from the gun. Gravity can no longer help us by allowing the empty magazine to drop free.Time and movement is wasted because the support hand needs to assist the mag from the gun before it can retrieve a replacement. Since we cannot see the magwell in the dark anyway, it is pointless to conduct an emergency reload in the workspace to begin with. The procedure only works in the light. If it does not work in the dark, should we still be using it? An emergency reload is a fundamental skill. The procedure for executing it should be just as effective in the dark as it is in the light.

Let’s Break It Down

1. Safe the weapon and tuck the stock under the arm if using a rifle. If using a pistol, come to a compressed ready position. Regardless of the platform, the muzzle stays pointed downrange. Since we cannot see any of it in the dark, we avoid range scars by not tempting ourselves to look at the weapon in the light.

2. Hit the mag release button and gravity will allow the empty mag to fall free. At the same time, the support hand is retrieving a replacement magazine and moving it toward the empty gun. We want the weapon to remain empty for the least amount of time possible. Ideally, the fresh mag is getting funneled into the magwell as soon as the empty one clears it.

3. After the new magazine is fully seated, the weapon begins to be brought back up to the ready position while the support hand hits the bolt catch or power-strokes the slide. Accomplishing two tasks in a single motion is more efficient.

4. Reacquire and/or reengage the threat.

Conducting an emergency reload is a fundamental procedure in weapons handling. And while mundane on flat range at 1300 hours, it is a stress-inducing nightmare in the middle of a fight in the dark. And as much as we want to believe we will rise to the occasion, the sad truth is that we will always fall to our lowest level of training. Therefore, it is imperative that we interrogate every procedure we have, from the individual to the team and all the way up to the command level, to ensure it works in every condition.

This is also why it is important to look for anything that can give us an edge. Doing it in the dark is what I like to refer to as a “software solution.” We are specifically developing and training procedures that will work under the worst circumstances—every time. And while repeated good training reps are required to build good neural pathways that ensure we will perform, good hardware solutions will help, too.

A bolt-on magwell can help speed up a no-look reload. And there are several great options on the market for tactical magwells. A tactical magwell is going to be smaller and slimmer than its competition cousins. It is better suited to professional use.

Another fundamental skill is clearing malfunctions/stoppages. A stoppage is something none of us ever wants to encounter in the real world. But it is bound to happen at some point, so we better know how to clear it and get the gun back into the fight. And it is another skill I routinely see students struggle with in the dark. Again, they have only been taught and practice a procedure that works in the light. And since darkness robs us of our ability to see, and our various technologies are limited for seeing up close on the battlefield, we need to practice fundamentals that do not require us to look at the gun.

The first step that most instructors or institutions teach when faced with a mushy trigger (indicating a stoppage of some sort) is to roll the gun on its side and look at the ejection port to see what sort of malfunction is occurring. In the daylight we can see if the bolt is fully in battery—if we have a double feed or stovepipe, for example. But as with the reload, our ability to see in the dark is very limited. And more often than not, the blindly executed “tap, rack, bang” induces a second malfunction. So why not adopt a procedure that will work in all circumstances?

1. If faced with a malfunction, I am going to immediately attempt to put the weapon on safe and lock the bolt to the rear.

2. Knowing that most malfunctions are magazine-induced, I am not going to attempt to continue using the same mag. The offending magazine is stripped from the gun and discarded.

3. Using my support hand, I will finger the magwell all the way up to the upper receiver to knock loose any stuck rounds.

4. The charging handle is racked several times to ensure free movement of the bolt.

5. A fresh magazine is inserted and the weapon is brought back into battery.

If the situation permits, I will retrieve the discarded magazine and stow it to salvage rounds. This procedure will work day or night, rain or shine to get a gun back in the fight. I can even use this procedure to identify worse malfunctions, such as the dreaded Bolt Override. If the mechanical safety cannot be engaged and the bolt cannot lock to the rear, I will assume the malfunction needs more attention than I can provide under the circumstances. At that time, I will transition to my pistol until I am in a hardpoint where I can work on the problem to fix a more complex malfunction. Regardless, this procedure will work in the dark and the light.

Reloads and malfunction clearance are microcosms in the grand scheme of things. But they serve as examples for how to adapt and adopt fundamental procedures to do it in the dark. Darkness should be metric by which you and your team measure every procedure. Ask yourself if your patrolling and exterior movement can be done in the dark and the light. Do your door procedure and link-up protocols work under night vision goggles? Statistically, bad things happen at night more than they do during the day. So, reschedule your training sessions at night to ensure you can do it in the dark. If something isn’t working when the lights go out, fix it. Images by Jace Crosby, JW Ramp & the author

• Customized F-150 and motorcycle • Built as a platform to draw attention to PTSD • Driving/riding from Washington to Virginia to support ptsdfoundation.org The F-150 you see…

Static-position shooting is great for practicing marksmanship and its fundamentals, but those who are in the professional field understand that practicing single-position shooting is just the beginning. Shooter…

51st SCORE Baja 1000 807-mile loop race course Location: Baja California Peninsula The unmistakable notes of a high-strung motor being pegged at full throttle jolted me awake. I…

A key training objective I try to achieve when shooting is to always observe the effects of my bullet impacts on and around my target. I refer to…

Many people dream of leaving their careers to pursue their true passions, but most never take the leap. As for George Fernandez, he followed his heart and found…

I have to admit that black guns or guns of any single color for that matter, while classic and timeless, can be a bit stale to the eyes…

© 2026 UN12 Magazine

© 2026 UN12 Magazine

Wait! Don’t forget to